Continuous Peripheral Nerve Blocks

Author

Edward R. Mariano, MD, MAS (Clinical Research)

Chief, Anesthesiology and Perioperative Care Service and

Associate Chief of Staff for Inpatient Surgical Services

VA Palo Alto Health Care System

Associate Professor of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine

Stanford University School of Medicine

Introduction

Continuous peripheral nerve block (CPNB) techniques provide target-specific analgesia for a variety of surgeries.[1-5] Compared to single-injection nerve block techniques, CPNB involves the percutaneous insertion of an indwelling catheter in the proximity of a target nerve (also known as a perineural catheter) that acts as a conduit for a continuous local anesthetic infusion. The use of CPNB facilitates same-day discharge after many types of extremity surgery which would have required at least overnight admission for pain control only a few years ago. Even for patients who undergo knee or shoulder replacement surgery, CPNB analgesia decreases the time to achieve discharge criteria and may be continued outside of the hospital setting for patients eligible for ambulatory recovery.[4][6]

Placement methods for perineural catheters vary based on the nerve localization technique (electrical nerve stimulation versus ultrasound-guidance) and the specific type of equipment involved. CPNB procedures should be performed employing sterile technique in a location where standard noninvasive hemodynamic monitoring and an oxygen source are available. Intravenous sedation should be administered to ensure patient comfort when necessary in this monitored setting. While it is impossible to present all available placement techniques in one article, the following descriptions will serve as an overview and highlight the major differences between commonly-performed approaches. Please refer to the other sections of the website to review the surface anatomic landmarks and sonoanatomy for each nerve block location.

Nerve Stimulation Technique

Electrical nerve stimulation is a well-established method used to localize the target nerve by evoking an appropriate motor response from the muscles innervated by the nerve of interest. Based on surface anatomic landmarks (refer to other sections), a site for needle insertion is selected.

Technical Considerations

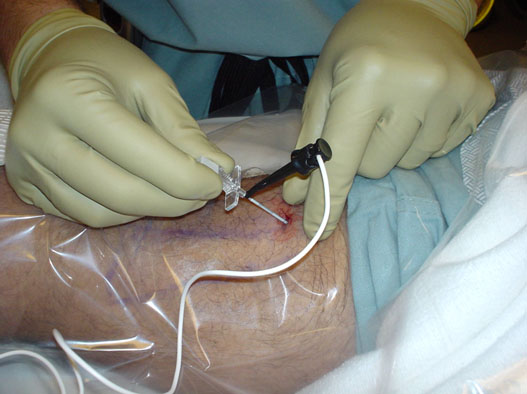

After sterile skin preparation and sterile draping, a local anesthetic skin wheal is raised at the planned insertion site of the CPNB catheter placement needle. The nerve stimulator (with lead attached to the insulated placement needle) is initially set at 1.2 mA, 2 Hz, and an impulse duration of 0.1 ms.[7-9] The CPNB placement needle is then inserted through the skin wheal and aimed cephalad toward the target nerve (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CPNB placement needle with nerve stimulator lead attached (example shown: posterior popliteal approach for sciatic CPNB).

If a motor response from the muscles innervated by the target nerve is not elicited within a reasonable depth of needle insertion, depending on the individual patient’s body habitus, the needle is withdrawn and redirected systematically in a direction perpendicular to the target nerve until the desired motor response is observed and maintained at a stimulating current amplitude < 0.5 mA.[1-2] At this point, stimulating CPNB techniques differ depending on the use of a stimulating versus a non-stimulating perineural catheter.

Stimulating Needle with Non-Stimulating Catheter

When inserting a non-stimulating perineural catheter (no conducting element within the catheter itself), the local anesthetic bolus is typically delivered via the placement needle,[1-2][10] followed by perineural catheter insertion 5 cm,10 up to 10 cm,[1-2] or even 20 cm11 beyond the needle tip. When employing this technique, it is possible to achieve a surgical block with the local anesthetic bolus yet fail to place the catheter in proximity to the nerve.[10][12] To increase the likelihood of accurate catheter placement, the distance of insertion beyond the needle tip should be minimized. Other investigators have also suggested placing the non-stimulating perineural catheter prior to injecting the local anesthetic bolus via the catheter.[3][13]

Stimulating Needle with Stimulating Catheter

Alternatively, a stimulating catheter that provides constant feedback in the form of an evoked motor response can be inserted through the placement needle.[9][14] After achieving the desired motor response via the placement needle at a stimulating current amplitude < 0.5 mA, an insulated catheter with a conducting element to deliver current through the tip is inserted through the needle and the stimulating lead transferred from needle to catheter (Figure 2). The stimulating perineural catheter is inserted up to 5 cm past the needle tip while maintaining the appropriate motor response in the distribution of the target nerve at or below a current amplitude of 0.8 mA.[7][9] The use of a stimulating catheter may increase perineural catheter placement accuracy and provide other clinical benefits when employing electrical stimulation alone.[15-17]

Figure 2. The stimulating lead is transferred from placement needle to an insulated perineural catheter with a conducting element that permits current delivery via the tip.

Ultrasound Guided Technique

There has been increasing interest in the use of ultrasound (US) guidance for regional anesthesia, and many techniques using US alone for perineural catheter insertion have been described.[18-21] In general, perineural catheter insertion techniques employing US rely on short-axis or transverse imaging of the target nerve.[21-25]

Technical Considerations

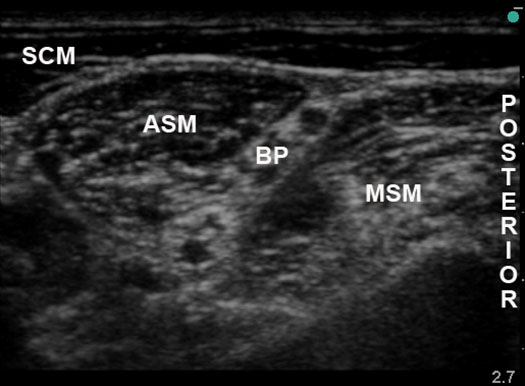

Short-axis imaging of the nerve enables the practitioner to identify the target nerve(s) and differentiate neural tissue from surrounding structures in cross-section (Figure 3). In addition, imaging the nerve in this fashion permits visual confirmation of local anesthetic injectate spread surrounding the target nerve.

Figure 3. Short axis image of a target nerve (example shown: interscalene approach to the brachial plexus); SCM = sternocleidomastoid muscle; ASM = anterior scalene muscle; MSM = middle scalene muscle; BP = brachial plexus

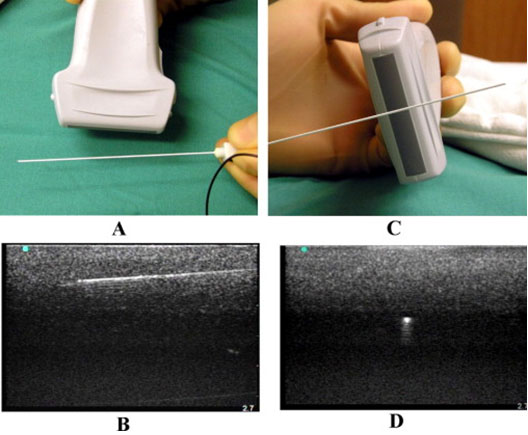

Long-axis or longitudinal imaging of the target nerve is feasible in certain anatomic sites only[26] while short-axis imaging can be performed for all common peripheral nerve block approaches. US-guided perineural catheter insertion techniques differ based on the location of placement needle insertion relative to the ultrasound transducer (Figure 4).[27]

Figure 4. (A) the in-plane needle insertion technique and (B) corresponding ultrasound image of the needle; (C) the out-of-plane needle insertion technique and (D) corresponding ultrasound image of the needle.

From Sites BD et al. RAPM 2007;32:412-418.

Out-of-Plane Needle Guidance and Catheter Insertion

After sterile skin preparation and sterile draping of the planned catheter insertion site and ultrasound transducer, a short-axis image of the target nerve is obtained. A local anesthetic skin wheal is raised distal to the mid-point of the ultrasound transducer. Needle tip position may be inferred based on visualization of tissue movement in the vicinity of the target nerve bundle[21][28] and injectate spread within the proper compartment.[19][21][28] A non-stimulating or stimulating perineural catheter is then inserted via the placement needle. Possible advantages of the out-of-plane technique include shorter distance from skin to nerve and a placement needle insertion site consistent with traditional stimulation techniques.

In-Plane Needle Guidance and Catheter Insertion

Compared to the out-of-plane approach, in-plane guidance allows the practitioner to visualize the entire needle including the tip throughout its trajectory toward the target nerve bundle.[18][22-23][25][29] Directing the needle within the ultrasound beam leads to a perpendicular orientation of the needle respective to the nerve when imaging the target in cross-section. The use of a flexible epidural-type catheter can facilitate accurate perineural catheter placement following injectate delivery via the placement needle when using US guidance alone.[18][22][23][25] It is possible to combine electrical stimulation with US guidance for perineural catheter insertion.[20][24] However, recent data do not support any advantage compared to US alone.[43-44]

Perineural Infusion Regimen

The optimal infusate and duration of perineural infusion have not been established. Most published studies employ ropivacaine and bupivacaine in various concentrations. In a study of hand grip strength during and after continuous interscalene block comparing ropivacaine 0.2% to bupivacaine 0.15%, subjects who received ropivacaine demonstrated better preservation of motor function at all time points and fewer paresthesias in the fingers.[30] Other studies comparing equipotent dosages of levobupivacaine and ropivacaine for CPNB have failed to demonstrate a difference in motor block.[31-32] Additives to plain local anesthetics for perineural infusion have not demonstrated any additional benefit.[33-34] It is apparent from clinical studies that perineural infusions exert varying degrees of analgesia and motor block at different anatomic sites.[7][35-36]

Studies comparing basal-only, basal-bolus, and bolus-only regimens for perineural infusions of 0.2% ropivacaine have demonstrated that the basal-bolus combination results in the optimal amount of analgesia, duration, and patient satisfaction when using infusion devices with fixed reservoir capacity.[9][14] Sample perineural infusion protocols are presented in Table 1. Ultimately, the dose of local anesthetic delivered, not concentration or rate individually, is the determinant of perineural infusion effects.[45-47] Although these are suggested starting doses, adjustments may be necessary to maximize analgesia and minimize motor block for the individual patient.

| Catheter Site | Basal Rate | Bolus Dose | Lockout Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brachial Plexus | 4–8 mL/hr | 4 mL | 30 min |

| Femoral or Saphenous Nerve | 4–6 mL/hr | 2–4 mL | 30–60 min |

| Lumbar Plexus | 4–6 mL/hr | 2–4 mL | 30–60 min |

| Sciatic Nerve | 6–8 mL/hr | 4 mL | 30–60 min |

The optimal duration of perineural infusion has not been determined. In a large multi-center prospective study of inpatient CPNB involving 8 institutions in France and Belgium and 1,416 patients, median infusion duration was 56 hours with a range from 2–7 days.[37] Longer durations of infusion are possible when managed carefully on the inpatient ward. At Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Dr. Buckenmaier and his military colleagues have reported an inpatient series of 361 CPNB catheters with a mean infusion duration of 9 days (range 1–34 days) and only 7 catheter-related infections (1.9%) which were limited to the insertion site with resolution following catheter removal.[38] Given the lack of available evidence to formulate guidelines for infusion duration on an ambulatory basis, outpatient CPNB catheters should be removed following 2–3 days of infusion similar to published research protocols.

Outpatient CPNB Management

The decision to send a patient home with a portable perineural infusion should be made very carefully as not every patient eligible for regional anesthesia is a good candidate for outpatient CPNB. For the right patients, outpatient CPNB techniques have demonstrated analgesic benefits for moderately-painful extremity surgeries based on the results of randomized, placebo-controlled investigations.[5][8][10] Furthermore, patients with local anesthetic perineural infusions at home suffer fewer side effects including sleep disturbances,[5][8][10] leading to a better quality of recovery.

A survey of patients who underwent CPNB at home revealed that once-daily telephone follow-up by a health care provider is the preferred amount of contact, and 98% of patients are comfortable removing their own CPNB catheters at home.[39] Only 4% would have liked a provider to remove his/her catheter while 43% would have been comfortable going home with only written instructions and no person-to-person contact.[39] A consistent complaint among those patients with perineural infusions is leakage from the catheter site (31%),[39] which should be explained to patients prior to discharging them home with CPNB catheters.

Institutions with outpatient catheter programs often send CPNB patients home with specific written instructions for their portable infusion device as well as provide a demonstration of the device function for the patient preoperatively (see Appendix). Patients who undergo upper extremity blocks should be discharged with a protective sling. Similarly, patients with femoral nerve or lumbar plexus blocks and persistent quadriceps weakness at the time of discharge should be sent home with a knee immobilizer, crutches, and written and verbal instructions not to bear weight on the affected extremity. Ambulatory CPNB patients should be discharged with a caretaker (family member or friend). Also included in the instruction sheet are expected CPNB issues (e.g., leakage and breakthrough pain) and contact information for a knowledgeable health care provider who is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Patients must have someone they can call should issues or questions arise at home, just as they would in the hospital. Routine telephone follow-up by a health care provider is performed on a daily basis until CPNB catheter removal, and each contact is documented.33 Patients can be given the opportunity to remove the catheter during the follow-up phone call when the infusion device reservoir is near exhaustion in order to provide real-time guidance if necessary.

Documentation and Billing

When nerve blocks are performed for postoperative pain, they can be considered separate from intraoperative anesthetic care. Therefore, it is worthwhile to design a distinct procedure note to document the details of these procedures, physician referral, and indication for the procedure (pain diagnosis).[40-42] When designing new forms, it is best to involve your managers to ensure compliance with hospital policies and mandates from regulatory agencies.

Use the correct current procedural terminology (CPT) code for each procedure (Table 2).[42]

| Perineural Catheter Site | CPT Code |

|---|---|

| Brachial Plexus (all approaches) | 64416 |

| Femoral Nerve | 64448 |

| Lumbar Plexus | 64449 |

| Sciatic Nerve (all approaches) | 64446 |

When submitting a claim for nerve block procedures performed for postoperative pain management, include the modifier -59 to identify this as a distinct procedural service.[41] For inpatients with continuous nerve block catheters, providers can also submit claims for daily evaluation and management (E&M) using 99231-99233 for established in-hospital consults.

Summary

CPNB techniques offer many benefits for the surgical outpatient with few drawbacks, but patients should be selected carefully. There are many techniques available for perineural catheter placement, and physicians are encouraged to obtain specialized training to ensure patient safety. Successful management of CPNB catheters at home should include detailed written instructions, daily telephone follow-up, and contact information for a health care provider familiar with these techniques and available when intervention becomes necessary.

References

- Grant SA, Nielsen KC, Greengrass RA, Steele SM, Klein SM: Continuous peripheral nerve block for ambulatory surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2001; 26: 209-14

- Klein SM, Grant SA, Greengrass RA, Nielsen KC, Speer KP, White W, Warner DS, Steele SM: Interscalene brachial plexus block with a continuous catheter insertion system and a disposable infusion pump. Anesth Analg 2000; 91: 1473-8

- Ilfeld BM, Ball ST, Gearen PF, Le LT, Mariano ER, Vandenborne K, Duncan PW, Sessler DI, Enneking FK, Shuster JJ, Theriaque DW, Meyer RS: Ambulatory continuous posterior lumbar plexus nerve blocks after hip arthroplasty: a dual-center, randomized, triple-masked, placebo-controlled trial. Anesthesiology 2008; 109: 491-501

- Ilfeld BM, Le LT, Meyer RS, Mariano ER, Vandenborne K, Duncan PW, Sessler DI, Enneking FK, Shuster JJ, Theriaque DW, Berry LF, Spadoni EH, Gearen PF: Ambulatory continuous femoral nerve blocks decrease time to discharge readiness after tricompartment total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, triple-masked, placebo-controlled study. Anesthesiology 2008; 108: 703-13

- Ilfeld BM, Morey TE, Enneking FK: Continuous infraclavicular brachial plexus block for postoperative pain control at home: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Anesthesiology 2002; 96: 1297-304

- Ilfeld BM, Vandenborne K, Duncan PW, Sessler DI, Enneking FK, Shuster JJ, Theriaque DW, Chmielewski TL, Spadoni EH, Wright TW: Ambulatory continuous interscalene nerve blocks decrease the time to discharge readiness after total shoulder arthroplasty: a randomized, triple-masked, placebo-controlled study. Anesthesiology 2006; 105: 999-1007

- Ilfeld BM, Loland VJ, Gerancher JC, Wadhwa AN, Renehan EM, Sessler DI, Shuster JJ, Theriaque DW, Maldonado RC, Mariano ER: The effects of varying local anesthetic concentration and volume on continuous popliteal sciatic nerve blocks: a dual-center, randomized, controlled study. Anesth Analg 2008; 107: 701-7

- Ilfeld BM, Morey TE, Wang RD, Enneking FK: Continuous popliteal sciatic nerve block for postoperative pain control at home: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Anesthesiology 2002; 97: 959-65

- Ilfeld BM, Thannikary LJ, Morey TE, Vander Griend RA, Enneking FK: Popliteal sciatic perineural local anesthetic infusion: a comparison of three dosing regimens for postoperative analgesia. Anesthesiology 2004; 101: 970-7

- Ilfeld BM, Morey TE, Wright TW, Chidgey LK, Enneking FK: Continuous interscalene brachial plexus block for postoperative pain control at home: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Anesth Analg 2003; 96: 1089-95

- Capdevila X, Biboulet P, Morau D, Bernard N, Deschodt J, Lopez S, d'Athis F: Continuous three-in-one block for postoperative pain after lower limb orthopedic surgery: where do the catheters go? Anesth Analg 2002; 94: 1001-6

- Salinas FV: Location, location, location: Continuous peripheral nerve blocks and stimulating catheters. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2003; 28: 79-82

- Borgeat A, Dullenkopf A, Ekatodramis G, Nagy L: Evaluation of the lateral modified approach for continuous interscalene block after shoulder surgery. Anesthesiology 2003; 99: 436-42

- Ilfeld BM, Morey TE, Enneking FK: Infraclavicular perineural local anesthetic infusion: a comparison of three dosing regimens for postoperative analgesia. Anesthesiology 2004; 100: 395-402

- Salinas FV, Neal JM, Sueda LA, Kopacz DJ, Liu SS: Prospective comparison of continuous femoral nerve block with nonstimulating catheter placement versus stimulating catheter-guided perineural placement in volunteers. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2004; 29: 212-20

- Rodriguez J, Taboada M, Carceller J, Lagunilla J, Barcena M, Alvarez J: Stimulating popliteal catheters for postoperative analgesia after hallux valgus repair. Anesth Analg 2006; 102: 258-62

- Casati A, Fanelli G, Koscielniak-Nielsen Z, Cappelleri G, Aldegheri G, Danelli G, Fuzier R, Singelyn F: Using stimulating catheters for continuous sciatic nerve block shortens onset time of surgical block and minimizes postoperative consumption of pain medication after halux valgus repair as compared with conventional nonstimulating catheters. Anesth Analg 2005; 101: 1192-7

- Sandhu NS, Capan LM: Ultrasound-guided infraclavicular brachial plexus block. Br J Anaesth 2002; 89: 254-9

- Swenson JD, Bay N, Loose E, Bankhead B, Davis J, Beals TC, Bryan NA, Burks RT, Greis PE: Outpatient management of continuous peripheral nerve catheters placed using ultrasound guidance: an experience in 620 patients. Anesth Analg 2006; 103: 1436-43

- Mariano ER, Afra R, Loland VJ, Sandhu NS, Bellars RH, Bishop ML, Cheng GS, Choy LP, Maldonado RC, Ilfeld BM: Continuous interscalene brachial plexus block via an ultrasound-guided posterior approach: a randomized, triple-masked, placebo-controlled study. Anesth Analg 2009; 108: 1688-94

- Fredrickson MJ, Ball CM, Dalgleish AJ, Stewart AW, Short TG: A prospective randomized comparison of ultrasound and neurostimulation as needle end points for interscalene catheter placement. Anesth Analg 2009; 108: 1695-700

- Mariano ER, Cheng GS, Choy LP, Loland VJ, Bellars RH, Sandhu NS, Bishop ML, Lee DK, Maldonado RC, Ilfeld BM: Electrical stimulation versus ultrasound guidance for popliteal-sciatic perineural catheter insertion: a randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009; 34: 480-5

- Mariano ER, Loland VJ, Bellars RH, Sandhu NS, Bishop ML, Abrams RA, Meunier MJ, Maldonado RC, Ferguson EJ, Ilfeld BM: Ultrasound guidance versus electrical stimulation for infraclavicular brachial plexus perineural catheter insertion. J Ultrasound Med 2009; 28: 1211-8

- Mariano ER, Loland VJ, Ilfeld BM: Interscalene perineural catheter placement using an ultrasound-guided posterior approach. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009; 34: 60-3

- Mariano ER, Loland VJ, Sandhu NS, Bellars RH, Bishop ML, Afra R, Ball ST, Meyer RS, Maldonado RC, Ilfeld BM: Ultrasound guidance versus electrical stimulation for femoral perineural catheter insertion. J Ultrasound Med 2009; 28: 1453-60

- Tsui BC, Ozelsel TJ: Ultrasound-guided anterior sciatic nerve block using a longitudinal approach: "expanding the view". Reg Anesth Pain Med 2008; 33: 275-6

- Sites BD, Brull R, Chan VW, Spence BC, Gallagher J, Beach ML, Sites VR, Hartman GS: Artifacts and pitfall errors associated with ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia. Part I: understanding the basic principles of ultrasound physics and machine operations. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2007; 32: 412-8

- Fredrickson MJ, Ball CM, Dalgleish AJ: A prospective randomized comparison of ultrasound guidance versus neurostimulation for interscalene catheter placement. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009; 34: 590-4

- Antonakakis JG, Sites BD, Shiffrin J: Ultrasound-guided posterior approach for the placement of a continuous interscalene catheter. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009; 34: 64-8

- Borgeat A, Kalberer F, Jacob H, Ruetsch YA, Gerber C: Patient-controlled interscalene analgesia with ropivacaine 0.2% versus bupivacaine 0.15% after major open shoulder surgery: the effects on hand motor function. Anesth Analg 2001; 92: 218-23

- Casati A, Borghi B, Fanelli G, Montone N, Rotini R, Fraschini G, Vinciguerra F, Torri G, Chelly J: Interscalene brachial plexus anesthesia and analgesia for open shoulder surgery: a randomized, double-blinded comparison between levobupivacaine and ropivacaine. Anesth Analg 2003; 96: 253-9

- Borghi B, Facchini F, Agnoletti V, Adduci A, Lambertini A, Marini E, Gallerani P, Sassoli V, Luppi M, Casati A: Pain relief and motor function during continuous interscalene analgesia after open shoulder surgery: a prospective, randomized, double-blind comparison between levobupivacaine 0.25%, and ropivacaine 0.25% or 0.4%. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2006; 23: 1005-9

- Ilfeld BM, Enneking FK: Continuous peripheral nerve blocks at home: a review. Anesth Analg 2005; 100: 1822-33

- Ilfeld BM, Morey TE, Enneking FK: Continuous infraclavicular perineural infusion with clonidine and ropivacaine compared with ropivacaine alone: a randomized, double-blinded, controlled study. Anesth Analg 2003; 97: 706-12

- Ilfeld BM, Le LT, Ramjohn J, Loland VJ, Wadhwa AN, Gerancher JC, Renehan EM, Sessler DI, Shuster JJ, Theriaque DW, Maldonado RC, Mariano ER, Horlocker TT: The effects of local anesthetic concentration and dose on continuous infraclavicular nerve blocks: a multicenter, randomized, observer-masked, controlled study. Anesth Analg 2009; 108: 345-50

- Le LT, Loland VJ, Mariano ER, Gerancher JC, Wadhwa AN, Renehan EM, Sessler DI, Shuster JJ, Theriaque DW, Maldonado RC, Ilfeld BM: Effects of local anesthetic concentration and dose on continuous interscalene nerve blocks: a dual-center, randomized, observer-masked, controlled study. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2008; 33: 518-25

- Capdevila X, Pirat P, Bringuier S, Gaertner E, Singelyn F, Bernard N, Choquet O, Bouaziz H, Bonnet F: Continuous peripheral nerve blocks in hospital wards after orthopedic surgery: a multicenter prospective analysis of the quality of postoperative analgesia and complications in 1,416 patients. Anesthesiology 2005; 103: 1035-45

- Stojadinovic A, Auton A, Peoples GE, McKnight GM, Shields C, Croll SM, Bleckner LL, Winkley J, Maniscalco-Theberge ME, Buckenmaier CC, 3rd: Responding to challenges in modern combat casualty care: innovative use of advanced regional anesthesia. Pain Med 2006; 7: 330-8

- Ilfeld BM, Esener DE, Morey TE, Enneking FK: Ambulatory perineural infusion: the patients' perspective. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2003; 28: 418-23

- Gerancher JC, Viscusi ER, Liguori GA, McCartney CJ, Williams BA, Ilfeld BM, Grant SA, Hebl JR, Hadzic A: Development of a standardized peripheral nerve block procedure note form. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2005; 30: 67-71

- Greger J, Williams BA: Billing for outpatient regional anesthesia services in the United States. Int Anesthesiol Clin 2005; 43: 33-41

- Mariano ER: Making it work: setting up a regional anesthesia program that provides value. Anesthesiol Clin 2008; 26: 681-92

Gandhi K, Lindenmuth DM, Hadzic A, Xu D, Patel VS, Maliakal TJ, Gadsden JC. J Clin Anesth. 2011 Dec;23(8):626-31.

Farag E, Atim A, Ghosh R, Bauer M, Sreenivasalu T, Kot M, Kurz A, Dalton JE, Mascha EJ, Mounir-Soliman L, Zaky S, Ali Sakr Esa W, Udeh BL, Barsoum W, Sessler DI. Anesthesiology. 2014 Aug;121(2):239-48.

Madison SJ, Monahan AM, Agarwal RR, Furnish TJ, Mascha EJ, Xu Z, Donohue MC, Morgan AC, Ilfeld BM. Br J Anaesth. 2014 Sep 23. pii: aeu333. [Epub ahead of print]

Bauer M, Wang L, Onibonoje OK, Parrett C, Sessler DI, Mounir-Soliman L, Zaky S, Krebs V, Buller LT, Donohue MC, Stevens-Lapsley JE, Ilfeld BM. Anesthesiology. 2012 Mar;116(3):665-72.

Ilfeld BM, Moeller LK, Mariano ER, Loland VJ, Stevens-Lapsley JE, Fleisher AS, Girard PJ, Donohue MC, Ferguson EJ, Ball ST. Anesthesiology. 2010 Feb;112(2):347-54.

Appendix

Continuous Nerve Block Catheter Instructions

- It is normal for your fingers/toes to be numb until the morning after surgery—you do not need to do anything.

- A health-care provider will call you for daily follow-up.

When you have pain

- Push the bolus button on the pump and wait 15 minutes for the effect.

- If you still have pain after 15 minutes, take 1-2 pain pills prescribed by your surgeon.

- The bolus button will work only one time every 30 minutes, so you cannot mistakenly give yourself too much medicine.

If any of your fingers/toes become completely numb

- It is normal for your fingers/toes to feel unusual. However, if there is any finger/toe that you cannot feel, you need to turn the pump off until you regain feeling:

- Hold the “on/off” button down for 8 seconds.

- The numbers in the digital readout (window) will disappear and be replaced by the word “OFF.”

- Later in the day/night, when you can feel someone else touching all of your fingers/toes, turn the pump back on:

- Press the “on/off” button.

- The pump should start up again. The pump is running if the digital black “droplet” appears in the digital display (window) moving top to bottom.

- If your pump is off for more than 3 hours and you still cannot feel one or more of your fingers/toes, call your health-care provider.

If your pump displays an error message

- Turn the pump off by holding the “on/off” button for 8 seconds.

- Call your health-care provider.

Other Instructions

- Youmust not driveany vehicle or operate potentially dangerous machinery while you have your catheter in place.

- Please keep your sling and/or splint on unless doing physical therapy.

- Very rarely, the catheter may fall out. If this occurs, take 1-2 of your pain pills, turn off the infusion pump using the instructions above, and call your health-care provider.

- It is normal for fluid to leak from the catheter site. Put a cloth over the site to absorb the extra fluid.

- Do not do not get the catheter, pump, or your bandages wet.

Removing your nerve block catheter

- Since there are no stitches, removal is easy by you or your caretaker.

- Start by lifting the edges of the clear dressing to expose the catheter.

- When you can see the catheter insertion site, grasp the catheter close to the skin and pull until all of it comes out. You can expect to remove up to 10-15 cm of catheter.

- Inspect the tip of the catheter and confirm that the end is black or silver then you can dispose of the catheter in the trash.

- You do not need to cover the site after the catheter is removed.

- If you have any difficulty removing the catheter, please call the number below.

- Since the pump contains a battery, and California does not permit trash disposal of batteries, please use the pre-paid envelope to mail the pump back to the manufacturer.

If you notice any of the symptoms listed below, STOP the infusion pump and immediately call your physician:

- Rash or hives

- Numbness around the mouth

- Metallic taste

- Ringing in the ears

- Lightheadedness

- Nervousness

- Confusion

- Chest pain

- Twitching

- Convulsions / Seizures

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top